What’s slowing the inflation slowdown?

March 18, 2025

Good news! Inflation is slowing. The annualized pace of consumer inflation fell to 2.8 percent in February from 3 percent in January. For businesses, price growth was 3.2 percent, down from 3.7 percent.

We’re getting closer to the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target rate of inflation. But there’s another 2 percent touchstone that matters even more for inflation in the long term—productivity growth.

The long and the short of it

Labor productivity, defined as output per worker hour, is the economy’s superhero. Producing more with less leads to economic growth, higher wages, improved profitability, and—wait for it—lower inflation.

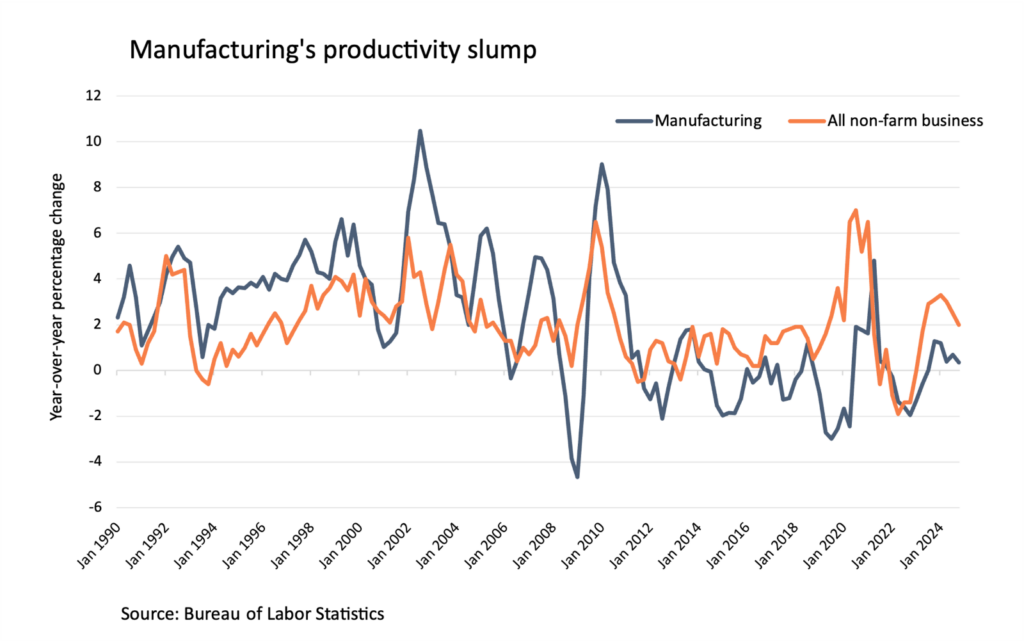

Since 1990, annual productivity growth for non-farm businesses has averaged 2 percent, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. That’s slower growth than we saw between 1947 and 2024, when productivity averaged 2.1 percent.

Think about it. Through the last three-plus decades of economic expansions, recessions, and innovation cycles (including the internet and personal computing), that’s the best we’ve done.

In 2024, productivity growth was an energetic 2.7 percent, the kind of gain that could pull inflation toward the Fed’s 2 percent sweet spot. However, the year ended soft, with productivity rising only 1.5 percent in the fourth quarter compared to a year ago.

But like all superheroes, productivity has its kryptonite.

The weak link

Since 1990, productivity in the manufacturing sector has averaged 2.2 percent annual growth. But in 2024, it was a sluggish 0.7 percent.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, productivity increased by a meager 0.3 percent. And when we look at sectors producing big-ticket durable goods such as refrigerators and airplanes, productivity actually fell by 1.1 percent from the same quarter a year earlier.

From innovation to production

Productivity can keep the economy growing without triggering inflation over the long term. In the short term, investments in productivity can be inflationary. Research and development take time and money. So does adoption and implementation.

Between the third quarter of 2023 and the third quarter of 2024, manufacturing’s contribution to GDP fell 0.3 percentage points, to 10 percent, the most recent data available. Compare that to the 13 percent the sector contributed to the U.S. economy 20 years ago.

Moreover, economists still struggle to accurately measure the contributions of productivity and technological progress to GDP. Digital goods such as streaming services, social media, and smartphones are prolific on Main Street and in corporate America, for example, but the digital goods share of GDP is about the same as it was in the 1980s, before these modern innovations even existed.

My take

Last week, I took a trip to the heart of Silicon Valley to witness a demonstration of cutting-edge robotics. As I was watching these amazing innovations, I couldn’t help but think what they’d mean for the Rust Belt where I grew up.

Technology’s promise, be it robots and artificial intelligence or electricity and the printing press, is to make workers more productive. We’re still waiting for that promise to be delivered to manufacturing.

And while there are no guarantees on what kind of change these innovations will deliver, lower and steadier inflation would be one welcome outcome.

The week ahead

Monday: Retail sales fell 1.2 percent in January from December, the biggest decline in two years. While frigid U.S. temperatures might be to blame, the 0.2 percent improvement in February was less than economists had hoped.

Tuesday: Census Bureau data on housing starts and permits might signal whether tariffs on construction inputs such as lumber, steel, and aluminum are affecting residential construction.

Wednesday: The unemployment rate edged down in March, giving Federal Reserve policymakers some breathing room when they meet Wednesday to decide the path of interest rates amid unsettled trade policy and a slowdown in consumer spending.

Thursday: Homebuyers are facing higher prices and mortgage rates stuck between 6.5 percent and 7 percent. February data on existing home sales from the National Association of Realtors will show whether these twin headwinds have dampened demand as the spring housing market begins in earnest.