In my last Main Street Macro exploring the state of labor market turnover, I argued that a healthy job market requires a healthy level of churn. Employers need to have the ability to attract talented and skilled people with strong pay and better career prospects, and they need to be able to replace departing employees.

But how much turnover is too much? How much is enough?

In Part II of my analysis of labor market churn, I looked at worker turnover by calendar month, industry, and employer size. The latter delivered a surprise: Small and large employers might be experiencing two very different labor markets.

The January effect

Each year, January marks a reset in the labor market. It’s when the largest share of workers is in motion as people leave old jobs for new prospects. January also is when employers reset hiring plans after the seasonal December dip in overall employment.

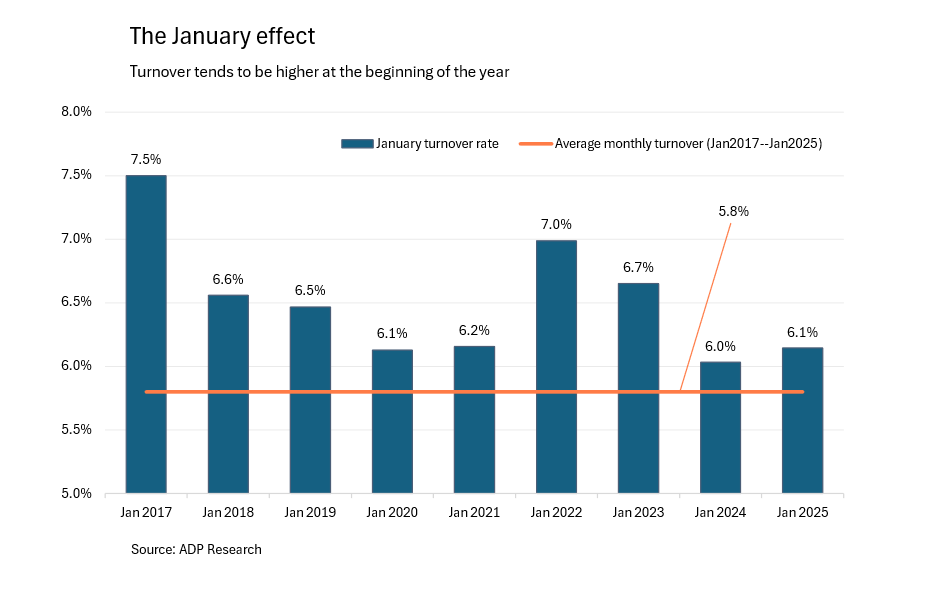

In the eight years that ADP Research has measured turnover, January is the month with the highest churn.

Generally, churn moves in reverse tandem with the unemployment rate. When labor market conditions are improving, workers are incentivized to seek new opportunities and employers dial up hiring. Turnover goes up, and unemployment trends lower.

In 2017, the January turnover rate—the share of workers who separate from a company during a given time period—hit 7.5 percent, the highest recorded in our eight-year time series outside of the immediate two-month aftermath of the pandemic shutdown in April and May of 2020.

U.S. economic growth was sluggish that year, with GDP expanding just 0.7 percent in the first quarter. But that high level of churn was a signal that the labor market was improving.

Over the next three years, the unemployment rate fell from 4.7 percent in January 2017 to a 50-year low of 3.5 percent in February 2020. Turnover soared in 2022 during the great resignation.

More recently, we’ve had two back-to-back years of steady churn. In January, turnover rose to 6.1 percent, in line with the 6 percent posted in January 2024 and the 5.8 percent monthly average over the eight-year series.

The industry variance

Turnover varies by sector for three primary reasons

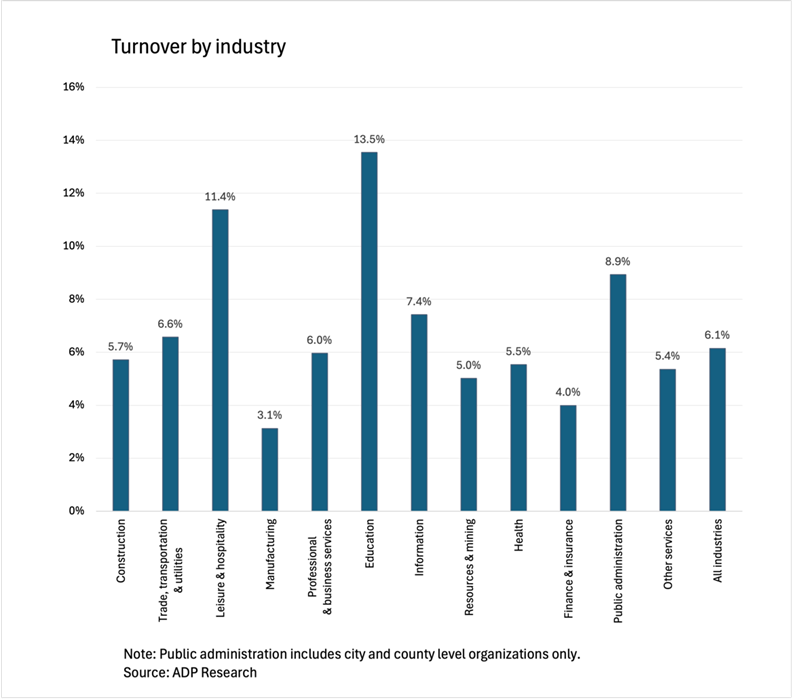

First, some industries hire at regular frequencies during the year. Those with the highest turnover are education, and leisure and hospitality, both of which tend to hire at the beginning of the year and during summer. This pattern partially explains their high turnover.

Growth prospects also play a role. In January, we reported that consumer-facing industries including leisure and hospitality were a big driver of job creation. Plentiful or meager opportunities partially explain sectoral differences in churn.

The third factor is worker age. Leisure and hospitality has the youngest workforce of the sectors we track, manufacturing the oldest. Younger workers tend to be more mobile and contribute to higher turnover.

The employer size dichotomy

Finally, employer size plays a role in turnover. Here’s where recent data has been unusual compared to past patterns.

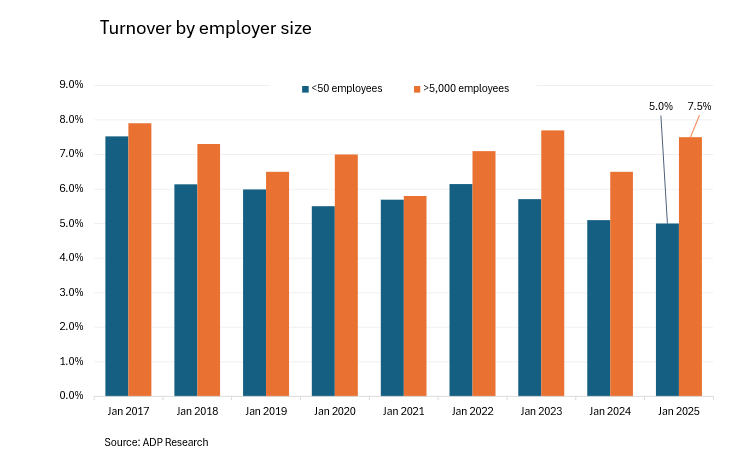

Look at the smallest and biggest employer categories in our data. The smallest firms have fewer than 50 employees. The largest have more than 5,000.

Since 2017, the smallest firms have become beacons of stability, with very low levels of churn. For these employers, the turnover rate fell from 7.5 percent in January 2017 to 5.1 percent in January 2024 and 5 percent in January 2025, two months of very low churn.

In contrast, churn is on the rise among the largest employers, jumping from 6.1 percent in January 2024 to 7.5 percent in January 2025. The 2.5 percentage-point difference in turnover between small and large firms is the largest we’ve seen in eight years of data.

My Take

Most changes in turnover are attributable to routine hiring patterns. What’s different now is the growing dichotomy between the smallest and largest employers.

In 2017, churn at big and small firms was high, but about the same. This year, those two groups are moving in different directions as turnover at large firms far outpaces that at small ones.

Turnover for the smallest firms has been low and stable for the past two years while large firm turnover has accelerated, jumping a full percentage point. Any movement in turnover at the largest firms has an amplified impact on overall employment due to the large headcount of these organizations.

The upshot: When it comes to turnover, two extremes have emerged. One signals ongoing stability. The other suggests that high turnover is far from over.

The week ahead

Tuesday: The Bureau of Labor Statistics releases January results of its Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS. In 2024, job openings stabilized at a healthy rate. Will that stability continue in 2025, or are employers recalibrating their recruitment efforts?

Wednesday: The BLS releases the Consumer Price Index. Inflation readings have been mixed, with the Federal Reserve’s go-to measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, trending down while CPI ticked up in January. Spending and sentiment data suggest that consumers are faltering under the weight of steady price increases.

Thursday: Initial jobless claims, a weekly proxy for layoffs, will receive lots of attention from economists looking for the effects of federal policy changes on employment. Economists also will be focused on any increased cost of inputs as measured by the Producer Price Index.

Friday: The University of Michigan releases its consumer sentiment survey for February. Downbeat consumer sentiment has become a fact of the economy over the last couple of years. What’s new is a resurgent expectation among consumers that inflation is set to tick up again, prompting new concerns about the outlook for consumer spending