Economic news has been dominated by two T words this year: Technology and tariffs. But there’s another T word that promises to have a far greater impact on the job market and inflation: Turnover.

Turnover, or labor market churn, is the rate at which employees leave their jobs and are replaced by new hires. This week, I’ll tell you about the state of employee turnover. In the next Main Street Macro, I’ll dig into specific industries and explore what labor market churn means for the U.S. economy.

Churn and the job market

Companies hire for one of two reasons: To increase headcount or to maintain it when workers depart. When economists assess the health of the job market, they tend to emphasize the former—the number of jobs created each month.

Yet just as important for the long-term health of the labor market is the degree of churn, the rate at which new hires replace exiting employees. High turnover can push up wages and other labor costs borne by businesses. Low turnover can stifle innovation and signal lackluster business growth and employment opportunities.

Post-pandemic churn

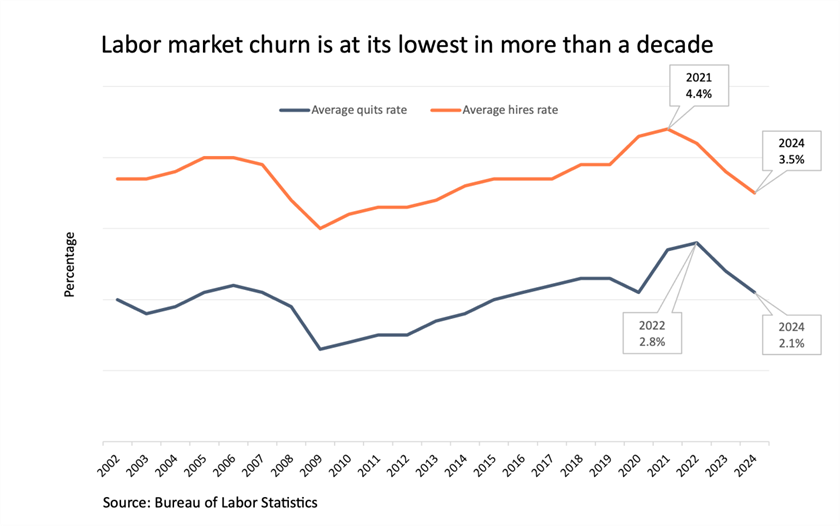

Two measures of labor market churn are quits and hires, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes in the monthly Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey of businesses.

The quits rate measures the percentage of workers who voluntary left their jobs in any given month, calculated by dividing the number of quits by total employment. The hires rate is the ratio of new hires to total employment each month.

When both indicators are high, it means people are quitting to take advantage of career opportunities and employers are hiring rapidly. One example was the great resignation of 2021, when both the quits and hires rates soared. Employers hired rapidly in 2021 and 2022. Between 2020 and 2022, the hires rate averaged more than 4 percent for the first time in recorded history. The quits rate peaked at 2.8 percent in 2022, capping a period of peak labor market churn.

The Big Stay? Or just stability?

Over the past two years, the great resignation has been replaced by the big stay. In December 2024, the quits and hires rates stood at 1.9 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively. These are the lowest rates of churn since 2013, when the unemployment rate was 7 percent, job prospects were dim, and employers were slow to hire.

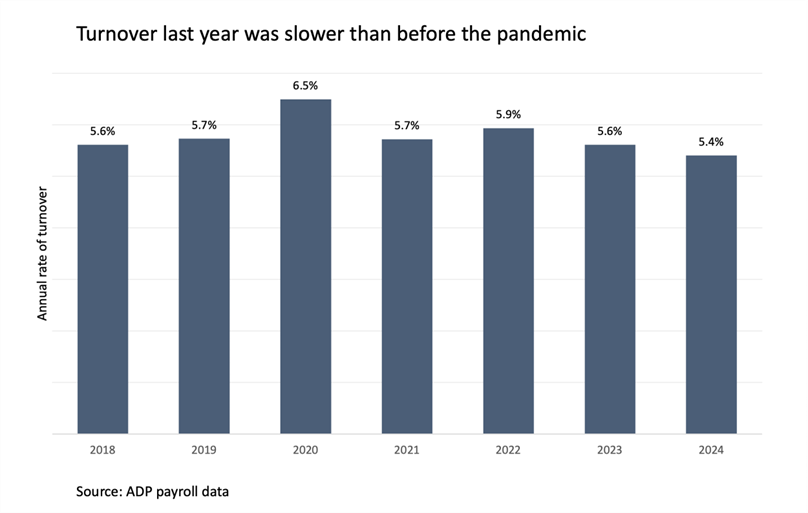

While BLS relies on a survey of businesses to collect this information, we can calculate turnover using ADP payroll data to compare the number of employees who leave their employers in the current month to the number of total employees in the previous month.

By our measure, labor market churn hit a record high of 11 percent in April and May of 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. But by 2024, turnover averaged just 5.4 percent, lower than it was before the pandemic. Both BLS survey data and ADP private-sector payroll data suggest the same trend: Turnover has slowed over the last two years.

My take

A slowdown in turnover could signal that workers are reluctant to leave their current employers and that private sector employers are reluctant to let workers go.

Over the long term, this is not ideal. Stability is a good thing, especially after the tumult of the pandemic, but a healthy job market requires a healthy amount of churn. Employers need to be able to attract talented and skilled people with higher-paying jobs and better career prospects, and they need to be able to replace departing employees.

In part two of this series on turnover, I’ll look at how churn varies by industry and what that means for the labor market in 2025.

The week ahead

Wednesday: The Census Bureau will release data on January new home sales. After hitting a low of 3.3 months in October 2020, the supply of new homes for sale has rebounded. Inventory hit 8.5 months in December, surpassing pre-pandemic levels. The effect of all this new home supply: home prices down 2 percent from a year ago.

Thursday: Census will issue estimates on durable goods orders an inventories. Durable goods, which are defined as items with a lifespan of three years or more, are purchases that households and businesses are the most likely to postpone. Aluminum and steel tariffs scheduled to take effect next month could drive up the cost of housing, according to the National Association of Home Builders, and might drive up prices on other big-ticket items such as cars and appliances. The question is whether businesses and consumers will try to get ahead of tariff-driven price increases by making purchases now or wait things out, possibly for lower interest rates.

Friday: Inflation’s sister indicators—the Consumer Price Index and Producer Price Index—both

edged up last month. But the components of these measures that feed into the Federal

Reserve’s preferred measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, could tilt this reading lower. That would be a big win for the wait-and-see Fed and for the Main Street economy, which is still waiting to catch a break on higher-for-longer price growth.

I’ll also be watching the Census Bureau report on wholesale inventories, which have been edging down the past few months. Dwindling inventories are usually a sign of robust consumer demand, and a favorable data release this week could offset emerging concerns about consumers