MainStreet Macro: Wages go prime time: Part 1

July 11, 2022

|

Friday’s payroll report surprised markets, with a strong 372,000 new jobs added to the U.S. economy in June. It was a positive print, but Wall Street’s reaction was downbeat.

That’s because, for markets, inflation trumps jobs as the top economic concern – a hot labor market ups the risk of worsening already high price increases. On Tuesday, we’ll get an update on where prices are headed.

Bridging the jobs and inflation reports is wage growth, a critical economic indicator that has become even more important. The trajectory of wages will help determine whether the Federal Reserve can put the brakes on rising prices without skidding the economy into recession.

To that end, central bank policymakers are eying one economic data point with unprecedented intensity: The proportion of job openings to the number of unemployed workers.

That ratio is a barometer for how tight the job market is. Currently, there are about two jobs for every unemployed person – more than double the historic norm.

For the Fed, a positive outcome would be that its aggressive interest rate hikes prompt employers to cut job openings but not workers.

Here’s a quick refresher on the state of wages. Before the pandemic, wage growth, like inflation, was stubbornly slow. And the pace of wage growth plummeted in the early days of the pandemic as workers were furloughed and laid off in large numbers.

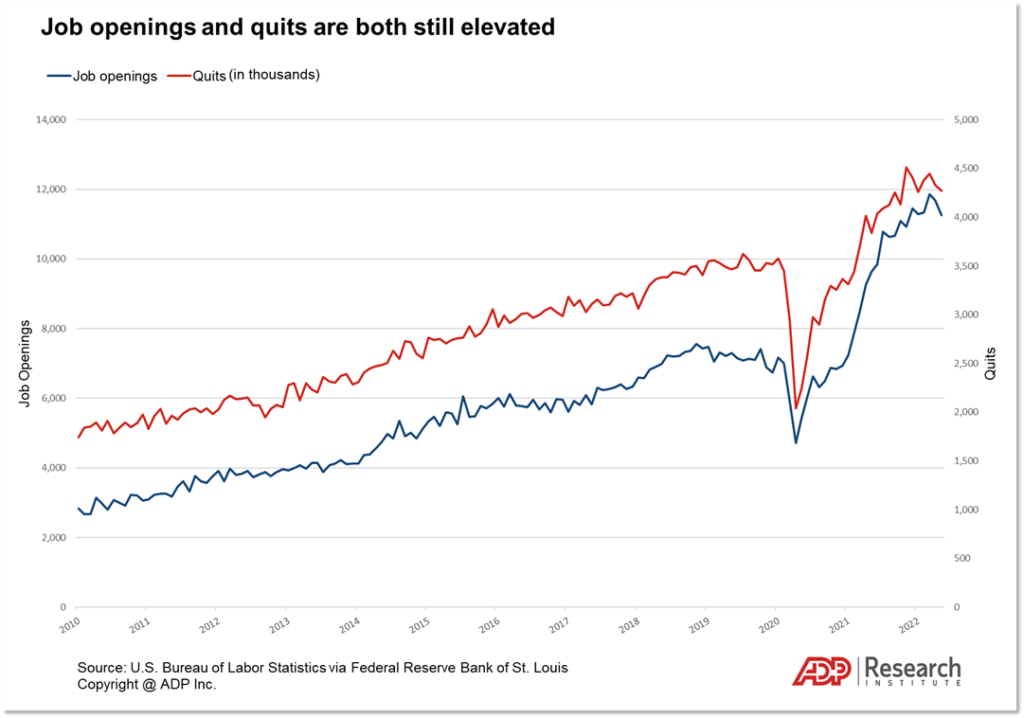

Since then, the job recovery has been defined by fierce competition for talent. Companies are still posting job openings at near-record levels, and workers flush with opportunity are changing jobs at a rapid clip, driving up their earnings.

Now, however, we see signs that the competition for talent might be easing up.

In May, the most recent data available, job postings edged down from the month before, and ADP Research Institute data suggests postings peaked in the spring. While the number of people quitting was largely unchanged in May from June, fewer openings in the coming months could calm the churn in the market. Fewer openings also could signal that companies are less willing to boost pay to lure workers.

While new hires can drive wage increases in a tight labor market, they typically represent less than 3 percent of all workers. For a fuller picture, ADP’s wage data watches individuals who stay in the same job for a year or more. Measuring a year’s worth of salary helps eliminate dips and bumps from month to month due to changes in hours worked, bonuses, commissions, or tips.

From May to June, the annual salary of a typical worker grew 7.5 percent for the second-straight month, to $55,167, our data show. That’s a $750 increase from this time last year. Wages began picking up in mid-2021 and have been strengthening ever since.

Leisure and hospitality sector showed the strongest wage gains last month. After the sector was hit hard by the pandemic, it’s been critical to the recovery, driving more than a third of all hiring last year. So far in 2022, however, hiring in the sector has slowed as a share of total job gains, going from 1 in 3 hires to 1 in 5.

Wages in this sector mirror that trend. Year-over-year gains have been in the double digits for the last eight months, but in March they peaked at 17.5 percent and have edged down since.

In June, leisure and hospitality wage growth was 14.9 percent year over year, down from 16.1 percent in May.

While leisure and hospitality gains slow, other sectors are gaining steam, with wage growth in the range of 7 percent to 10 percent in June, more than double the 3 percent to 4 percent growth rates posted last year.

My Take

Wages are a function of demand for talent and workers’ level of willingness to supply that talent. Demand has been strong for the past year, but supply has remained stubbornly low even as wages rise.

Yet even with strong recent wage gains, inflation north of 8 percent means that workers who have been with the same employer for years are losing ground to price increases.

If employers continue to increase pay for the same level of output per worker, not only will the economy slow, inflation will climb even higher, which could lead to stagflation. Stagflation occurs when the economy stagnates as inflation and unemployment stay persistently high.

That’s why Federal Reserve policymakers are eying the ratio of openings to workers with an intensity not seen before. Next week, Main Street Macro takes a look at wage trends around the country. Stay tuned.