MainStreet Macro: The Fed needs a sidekick

September 19, 2022

|

Last week, consumer inflation data told us two things. First, thanks to falling energy prices, overall inflation edged down, to 8.3 percent in August from 8.5 percent in July.

Second, other components of inflation accelerated, namely housing, food, and medical care.

But if we strip out the two most volatile components of the index – food and energy — we get a troubling picture: Inflation went up, not down, from the previous month.

That inflation measure – what’s known as core inflation — accelerated by 0.6 percent points in August, double the 0.3 percentage point increase in July from June.

Instead of containing itself to segments of consumer spending that were heavily affected by the pandemic and supply-chain bottlenecks, inflation is becoming broad-based and thus more persistent.

The Fed’s superpowers won’t save us

Usually, when we think of harnessing the menacing threat of inflation, we think of the Federal Reserve.

The Fed is our inflation-busting superhero, saving the day by raising short-term interest rates. But if you’re a fan of action movies like I am, you know that when superheroes save the day, they often leave damage in their wake.

In the movies, the damage typically amounts collapsed buildings and crushed cars. In the real world, it could be higher unemployment and a slowing economy.

This economic fallout occurs because, like many superheroes, the Fed can play defense only after a threat materializes, not before.

But, as I argue in an essay for the Peterson Foundation, the Fed doesn’t have to act alone.

Every superhero needs a good sidekick. In the world of economics, the federal government plays Robin to the Fed’s Batman. When it comes to inflation, congressional and executive branch fiscal superpowers can be deployed to play offense.

Fiscal policymakers can scout for tangled supply chains, then adopt policies to loosen those knots. By tackling supply constraints now, the legislative and executive branches can put the brakes on higher prices in the future.

The inflation villains: Housing and labor shortages

For an example of a supply chain failure, look no further than housing, which makes up about 40 percent of the Consumer Price Index.

Main Street currently is suffering from high rents and home prices because the housing market has been chronically undersupplied for more than a decade. That’s especially true for affordable housing, which affects working families.

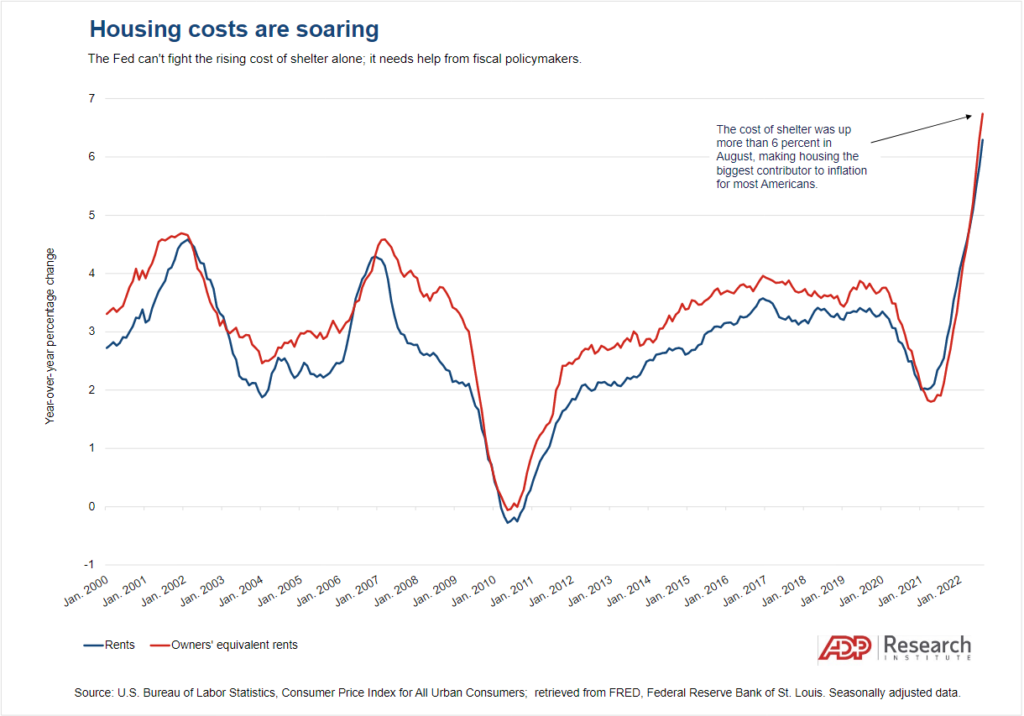

Over the past year, the cost of shelter has exploded for both renters and homeowners. Housing costs rose month-over-month by 0.7 percent in August, up from 0.5 percent in July.

Housing is one of the biggest budget items in the consumer pocketbook. Higher rents and mortgage payments can leave families with less money to buy food, gasoline, and other goods and services that also are increasing in cost.

There is no national policy to address current the housing affordability crisis. Absent action at the federal level, the housing market is regulated largely by city and county politicians who have little incentive to increase building density.

Also in short supply is labor. As we learn to live with the pandemic, worker shortages continue to hobble Main Street employers and increase the cost of doing business.

Over time, what we today call a worker shortage is more than likely to transition into a skills shortage, where the current crop of workers will lack the know-how demanded by employers.

Policies that expand the workforce – be it funding for up-skilling or career training — can help better connect workers to the jobs of the future.

My Take

We need a fiscal and monetary Dynamic Duo to take on our agitated economy and defend Main Street from the scourge of high inflation, both now and in the future. Federal spending now to educate and house our labor force would boost tax revenue and be a stabilizing influence against future inflation.