MainStreet Macro: Student debt: The other side of the mountain

October 24, 2022

|

The application process has begun! No, not for college admission, for student loan forgiveness.

Last week, the Biden administration opened the application process for debt forgiveness, the first step in the president’s three-part plan to help low- to middle-income borrowers saddled with big tuition bills.

There are no transcripts, standardized test scores, essays, or letters of recommendation required. Applicants for this program need to meet only one threshold: Debt holders must earn less than $125,000 a year in individual income or $250,000 in household income to be eligible. The payoff: up to $10,000 in debt forgiveness, or, for recipients of federal Pell Grants, which are distributed to students with financial need, up to $20,000.

The plan has generated plenty of controversy, and an appeals court put the program on hold Friday. But behind the debate over student debt forgiveness stands an even bigger problem.

Mountain or molehill?

President Joe Biden’s student debt relief plan lands at a sensitive time for the economy and its struggle with inflation. Big government spending helped avert a prolonged economic downturn during the pandemic, but it also probably contributed to a spike in consumer demand that helped drive up the cost of living. Student loan forbearance, a page in the government’s pandemic playbook, has been in place for two years.

In theory, erasing $10,000 or $20,000 in debt could trigger increased demand for TVs or vacations, the kind of spending behavior that could fuel further inflation. But debt forgiveness is less likely to increase spending the way direct government windfall payments did when they hit household mailboxes in 2020 and 2021.

Still, it’s an open question whether debt relief will cause a mountain- or molehill-sized surge in demand.

A steep climb gets steeper

Instead of focusing on inflation, let’s dig deeper into the problem of student debt. Back in 2020, I explained why Main Street should care about it. In the U.S., tuition loans grew a whopping 90 percent between 2010 and 2020, to more than $1.7 trillion.

That debt load is ballooning again because of a pandemic-driven payment hiatus on government issued student loans. By the end of last year, 66 percent of borrowers had flat or growing balances, compared to 48 percent by the end of 2019, according to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Before federal relief was rolled out in response to the pandemic, student debt had claimed the dubious record of having the highest rate of severe delinquencies, unseating credit cards for the title. So far this year, the student debt delinquency rate is still more than nine times the delinquency rate of mortgages.

The next hill to climb

Student debt and the rising cost of tuition have helped put college enrollment in decline, even with the return of classroom instruction and campus social life. Fall enrollment for undergraduates was down 1.1 percent this year compared to last year, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Undergraduate enrollment has fallen 4.2 percent since 2020.

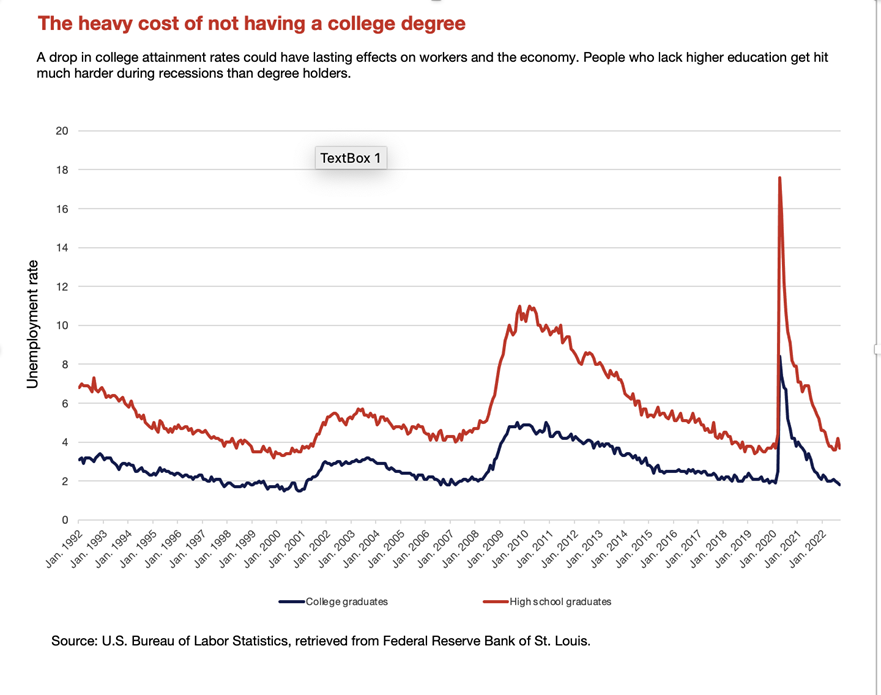

A drop in college attainment rates could have lasting effects on workers and the economy. For people with and without college degrees, unemployment was near record lows before and after the pandemic.

But during the pandemic, the unemployment rate for people without a college degree jumped to a staggering 17.6 percent in April 2020, compared to an elevated but much easier-to-swallow 7.6 percent for college graduates.

The phenomenon also occurred during the 2007-2009 recession, when workers without degrees experienced an unemployment rate of 11 percent, more than double the 4.9 percent unemployment among college graduates. It took a long time – nearly a decade – for wages to grow meaningfully higher than inflation for workers.

The upshot is that workers who don’t have a college degree are more vulnerable to recessions, both in terms of job losses and income growth.

My Take

For a long time, student loan debt was viewed as “good debt”. The investment in education was thought to be worth it. It meant a better job, perhaps an opportunity to be a homeowner and the potential to accumulate wealth. But as the cost of education has skyrocketed – it’s up nearly 30 percent over the last decade – college enrollment has slowed.

College degrees aren’t the only pathway to lofty financial goals. Vocational training is equally important. The larger point is that acquiring in-demand skills has become even more expensive in the presence of higher and rising interest rates and soaring tuition.

Debt relief might affect inflation a little or a lot, but waning college enrollment is all but guaranteed to take a big toll on the economy. Politicians debating the wisdom of student debt forgiveness perhaps should be putting their heads together to figure out how to maintain an educated workforce. That’s the other side of the student debt mountain.