MainStreet Macro: Another repercussion of Fed rate hikes: The dollar

September 26, 2022

|

The Federal Reserve last week took another aggressive whack at too-high inflation, raising its benchmark interest rate by three-fourths of a percentage point.

It’s the third time in a row the Fed has taken such a big step, and indications are it won’t be the last. Central bank policymakers have telegraphed that they plan to raise the federal funds rate by a combined 1.25 percentage points in their last two meetings of 2022.

Interest rates are an effective but blunt policy tool. Higher borrowing costs ripple throughout the economy, affecting stocks and bonds, home prices and mortgages, and trade in goods and services. Interest rates, in short, drive commerce.

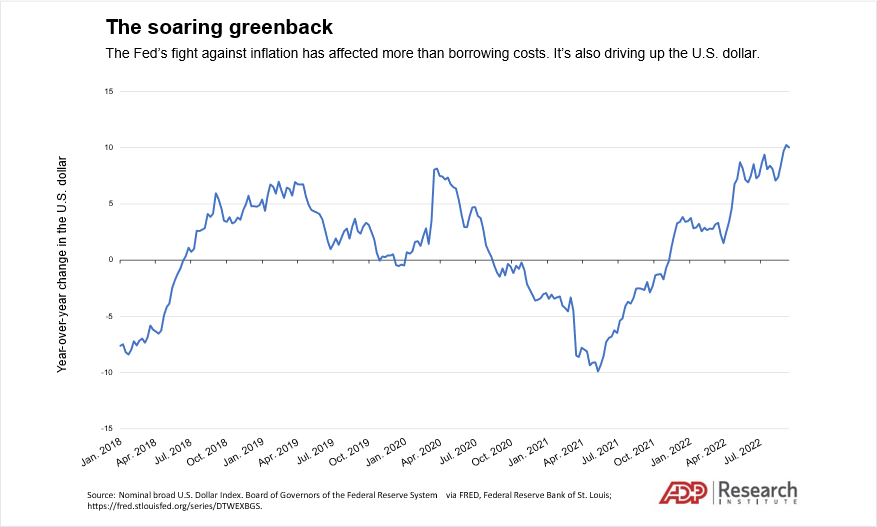

And there’s another place that monetary policy has an important impact – the global currency market. More specifically, Fed action can drive up the U.S. dollar, making it more valuable.

The dollar’s strength typically is measured against a basket of other major currencies such as the euro, British pound, or Japanese yen. Lately, the dollar has been outstripping its global economic peers – by a lot.

There are three reasons for the strengthening greenback. U.S. economic growth, though slower this year than last, its growth prospects are less risky than the regions in Europe and Asia because of the effects of the war in Ukraine and China’s coronavirus lockdowns.

The Fed also has been much more aggressive than its central banking peers in hiking short-term rates, which affect the supply and demand of dollars around the world.

Finally, the U.S. dollar is the world’s No. 1 safe-haven currency. As global growth slows, investors tend to park their money in Treasury bonds as a protective measure. Generally, Treasurys aren’t as profitable as stocks, but their modest, government-backed return is better than putting a wad of cash under a mattress.

The power – and peril – of a strong dollar

American travelers greet a strong dollar with glee. As the dollar appreciates, the rest of the world gets cheaper. Traveling abroad with a strengthening dollar in your wallet is like getting hotel rooms, meals, and cheesy souvenirs at a special American tourist discount.

And a strong dollar isn’t a boon just to travelers. The U.S., as one of the richest countries in the world, imports a lot more than it exports. Consumers generally benefit when the dollar rises in value because imports become comparatively less expensive.

But for businesses with overseas operations, the benefit of a strong dollar is less clear-cut. Yes, a strong dollar makes inputs sourced from overseas cheaper. At the same time, however, it increases the cost of U.S. goods and services to foreign consumers, which could hurt sales. And wares sold abroad in local currencies produce less revenue when translated back to dollars here at home.

The opposite also is true. As the dollar strengthens, other currencies are weakening. The yen is at a 24-year low against the U.S. dollar, and the euro is on par with the greenback for the first time in more than a decade.

While a strong dollar can agitate advanced economies, it can cause outright pain to poor and emerging-market nations.

Countries with unstable economies can’t borrow in their own currency because investors would charge exorbitant interest rates to assume the risk of a default. Instead, emerging markets frequently issue debt in dollar-denominated assets. And when the dollar gains value, it takes more of the local currency to repay those debts.

This interplay between the dollar and emerging market debt can curb investor interest, slow economic growth, and even trigger financial crises.

My Take

When I was a government economist, one of my primary roles was to conduct cost-benefit analyses for various policy options. Almost every policy you can imagine has a tradeoff between its cost and its benefits.

Fed interest rate policy is no different. Raising rates has the intended benefit of lowering inflation. Domestically, the unintended cost can be higher unemployment and slowing growth.

The Fed has made clear that it believes these costs to the U.S. economy are outweighed by the central bank’s mandate to keep inflation in check.

But while Fed policymaking targets our domestic economy, its impact is global. As the proverbial central banker to the world, when the Fed moves aggressively, other countries, both rich and poor, must adjust.

Central banks in other advanced countries can follow, if not match, the Fed’s actions, and raise rates too. But less-wealthy economies have fewer choices. In the global economy, they’re price-takers, unable to influence the market. That makes them vulnerable to disinvestment when the economic outlook sours.

As the Fed fights inflation, the dollar is the elephant in the room. Rising interest rates affect not only U.S. inflation and growth, but, through the dollar, economies world-wide.