Main Street Macro: What’s debt got to do with it?

September 23, 2024

|

The Federal Reserve’s move to cut its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point won’t likely be felt immediately by its primary targets, employers, and households.

Yes, the Fed has a mandate to promote full employment and price stability, but in practice it takes a long time for rate cuts to translate into more hiring and spending on Main Street.

Instead, the first people to feel the benefits of lower rates will be borrowers. Households and businesses will find it cheaper to fund purchases and investments, which eventually will lead to more hiring.

That’s the theory, anyway. To evaluate the potential impact of Fed rate cuts, we need to look at the current state of debt relative to income in key segments of the economy.

Consumer debt

Consumers drive the lion’s share of economic growth. As such, they’re the most important target of the Fed’s monetary strategy.

Central bank policymakers began raising the benchmark rate, which influences the cost of mortgages, credit cards and car loans, in March 2022. By September 2023, the federal funds rate had risen from 0.08 percent to 5.33 percent.

Still, consumers continued to borrow even at higher rates, and household debt rose 7 percent between the second quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2024. But household wealth, which measures the value of financial assets and home equity, grew even faster, rising 11 percent over the same period.

Not only has household net worth increased, real disposable income, which is after-tax income adjusted for inflation, is up 6 percent from two years ago, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This means that consumers are positioned to better bear the cost of higher interest rates.

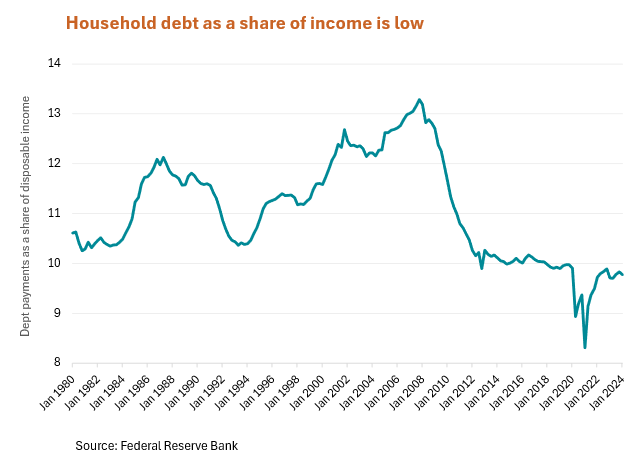

In fact, household debt payments, when measured as a share of disposable income, are back to their pre-pandemic average of less than10 percent. After sinking to a historic low during the pandemic when consumer spending dried up, payments have stabilized at a full percentage point below their historical norm of 11 percent.

This also means that the last two years of higher interest rates have failed to put a dent in consumer spending. Retail sales were strong in August, showing consumers holding up well in the face of higher prices and borrowing costs.

So, will lower rates encourage more debt and spending? Certainly. But will the impact on consumers be as great as it was when the Fed cut rates in 2008, when the ratio of debt payments to disposable income was at a 13.2 percent high? Probably not.

Corporate debt

Another big target for rate cuts are large employers, who are key players in the Fed’s full-employment mandate.

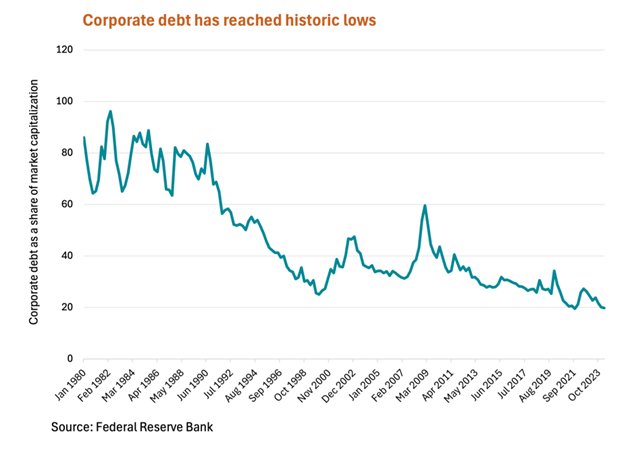

Rather than taking loans from banks, large employers borrow in the capital markets. One way to assess the health of this sector is to look at the ratio of corporate debt to corporate valuations, or market capitalization.

This ratio reached record lows this year largely because of strong market capitalization growth. One measure of the value of big companies, the S&P 500 index, was up a robust 17 percent in the last two years even in the face of higher-than-normal interest rates.

With large employers more capitalized than ever, will rate cuts jump-start corporate hiring? Maybe.

The labor market is in solid shape. Layoffs are near historic lows and the unemployment rate is below its historical average. That means the Fed rate cut probably won’t trigger a big hiring boom. But it could benefit smaller employers that depend on bank loans to finance growth and increase staffing.

Government debt

No review of debt would be complete without a look at the biggest borrower in the economy, the U.S. government.

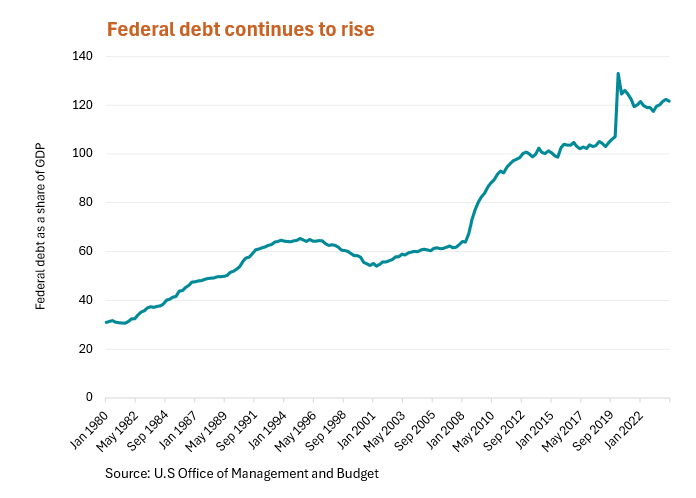

The ratio of U.S. debt to U.S. income, or GDP, has fallen since the throes of the pandemic, when the government unleased much-needed emergency funding to struggling businesses and households. The national debt is now 122 percent of GDP, much higher than historic or pre-pandemic averages.

And it’s expected to climb even higher, according to the Congressional Budget Office, primarily due to non-discretionary spending on Medicaid and Social Security.

As of August, 17 percent of all federal spending went toward interest rate payments, according to the Treasury Department. A Fed rate cut will lower borrowing costs, but it won’t solve the U.S. debt problem.

My take

Again, the theory works like this: The Fed cuts rates, lowering borrowing costs for employers and consumers, and stimulating a struggling economy. Consumers get room to spend more, and companies have incentive to hire.

But what if the economy isn’t struggling? What if consumers already are spending, and household debt compared to income is relatively low? What if big employers are operating in a balanced labor market and have record low debt relative to market values?

Lower borrowing costs will help Main Street spend more, but they won’t juice the economy as much as previous rate-cutting cycles.

The catch is government debt, which is the only economic ratio that hasn’t returned to a pre-pandemic normal. U.S. debt continues to soar, and Federal Reserve rate cuts can do only so much to help.

The Week Ahead

Tuesday: The first sector to watch for an effect of the Fed rate cut is housing. The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Home Price Index is reported with a two-month lag, but will be an important indicator to watch going forward. The question is whether cheaper borrowing makes housing more affordable, or if it spurs demand enough to drive prices even higher.

Thursday: Census Bureau data on orders for durable goods and an update on second quarter GDP from the Bureau of Economic Analysis will give us a signal of consumer health and tell us whether recent solid economic growth has held up.

Friday: The most important data point of the week is the PCE price index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. PCE for August will validate—or not—the Fed’s outsized rate cut and could set the tone for cuts to come.

And, in case you missed it: ADP Research is out with the third quarter issue of Today at Work. Learn which cities are good bets for young job-hunters, get a reality check on the toolbelt generation, dig into new data on wage garnishments, and more.