Main Street Macro: What could go wrong?

September 30, 2024

|

Last week’s economic data delivered a lot of good news. The Bureau of Economic Analysis confirmed that the economy grew at a solid 3 percent pace in the second quarter. Initial jobless claims, a measure of layoffs, fell to 218,000, the lowest level since May.

And the highlight of the week, inflation, edged below economist expectations to 2.2 percent, the lowest rate in three years, according to the Personal Consumption and Expenditures Price Index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure. Stripped of volatile food and energy prices, core inflation is still too high at 2.7 percent, but it’s closer to the Fed’s 2 percent target. This time last year it was 3.8 percent.

This economic landing doesn’t feel soft. It feels downright cushy.

What could go wrong? This week we’ll see how the job market stacks up to last week’s good news. Here are three indicators to watch.

Manufacturing

For someone trying to gauge the strength of the labor market, manufacturing isn’t the most obvious place to look. But two monthly private-sector surveys of purchasing managers and supply executives provide an important barometer of the job market outlook for three reasons.

First, if the job market is only as strong as its weakest link, then manufacturing is the sector to monitor for a break. The sector shed 24,000 jobs in August, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Continued weakness could have an outsized effect on the job market and push up the national unemployment rate.

Second, manufacturing is highly cyclical. It tends to grow as the economy expands and shrink when the economy slows. The sector, therefore, is one of the main beneficiaries of Fed rate cuts, which can lower the cost of production and increase profits.

In theory, manufacturing should be among the first sectors to respond to the recent Fed rate cut with stronger hiring.

Hours

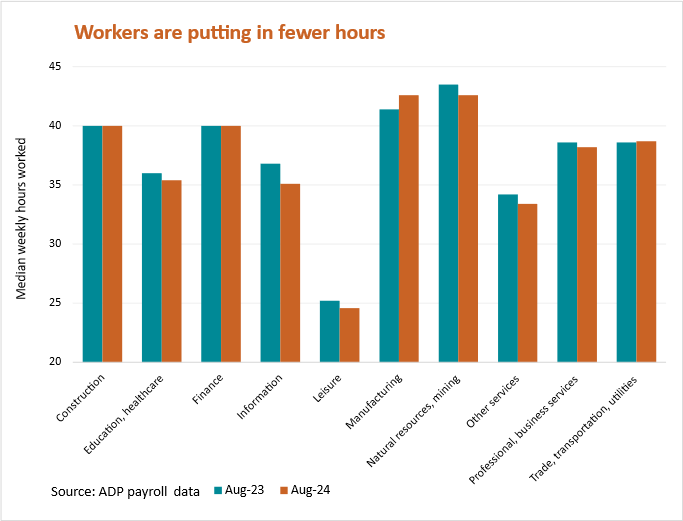

It’s been documented that even as employment has increased since 2020, average weekly hours worked have been falling. One reason is the dominance of hiring in leisure and hospitality, health care, and other service industries, which has contributed to a greater concentration of part-time jobs.

ADP’s own data shows that the share part-time work rose from 40.3 percent to 41.7 percent during the 12 months that ended in August. Even within leisure and hospitality, the typical workweek has shrunk over the past year.

Median hours worked in leisure and hospitality fell from 25.2 a week in August 2023 to 24.6 a week in August 2024. In education and health care, median hours worked fell from 36 to 35.4 a week. The information sector showed the biggest decline, from 36.8 hours a week to 35.1 hours.

A slowdown in hours worked among service providers might be an early warning sign of reductions in hiring.

Wage premium

One sign of a healthy labor market is when workers find it easier to land higher-paying jobs. As the wage premium between a typical worker’s old and new job grows, the labor market becomes tighter, with employer demand for workers outstripping worker supply. This imbalance pushes up wages.

ADP Pay Insights data tracks the pay of roughly 10 million individual workers, which allows us to see the difference in pay gains for people who stayed on the same job for at least 12 months and those who found new jobs during that same time period.

The wage growth premium between these job-changers and job-stayers peaked in spring 2022 at nearly 9 percent. By this past August, the difference had narrowed to only 2.5 percent.

If the wage premium shrinks further in September, it will indicate that workers are having more difficulty finding higher-paying jobs.

My Take

When it comes to the labor marker, we’re still in good-news territory. Layoffs are rare. Real wages are growing. Companies in aggregate continue to hire, albeit at a slower pace.

Against this backdrop, it will be more difficult to discern turning points in the health of the overall job market by relying solely on traditional employment indicators. Job openings, initial jobless claims, unemployment, and other measures that economists tend to consult are very important, but they lag fast-moving and finely grained changes by sector and at the worker level. The labor market picture comes into better focus when traditional indicators are supplemented with real-time, private-sector indicators like the ones discussed above. Together these measures provide a more comprehensive early warning system on what could go wrong in the job market.

The week ahead

Tuesday: To get a good sense of future employment among goods producers, I’m watching manufacturing surveys out today from the Institute for Supply Management and S&P Global, and data on construction spending from the Census Bureau. The two manufacturing surveys have been in the doldrums for months. Look for even a small boost in optimism and hiring now that Fed rate cuts are under way.

Wednesday: ADP releases its monthly National Employment Report and Pay Insights data. Of particular importance is the wage premium between job-stayers and job-changers. A smaller wage premium could signal that hiring will weaken in coming months. An increase would be good news on hiring.

Friday: The Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its monthly report on the national employment situation. Fed watchers will be watching the unemployment rate for a signal on future rate decisions.