Main Street Macro: Wages and hiring: It’s not as simple as you think

July 08, 2024

|

Last week’s run of jobs data made two things clear. The U.S. job market is cooling, and hiring is highly concentrated in just a few service sectors. Both these trends could have implications for wages, which could, in turn, have implications for the Federal Reserve.

Over the last three months, the ADP National Employment Report averaged 165,000 monthly private-sector job gains, compared to 347,000 over the same period last year. Bureau of Labor Statistics non-farm payroll data, which includes government jobs, averaged 177,000 over the past three months after Friday’s downward revision of 111,000 jobs in April and May. That’s down from an average 274,000 in monthly job creation during the second quarter of 2023.

But two other things are happening behind the scenes. As hiring slows, it’s concentrating in a handful of service sectors. Had it not been for a rebound in leisure and hospitality hiring in June, private-sector payrolls would have been downbeat. Hiring in government and healthcare produced more than 70 percent of BLS non-farm payroll gains for the month. Both ADP and BLS estimates show weakness in manufacturing.

And while hiring cools, wages, which will have a greater influence on the Federal Reserve’s interest rate decisions in the second half of this year, have gotten more complicated and will take longer to play out.

The role of wages

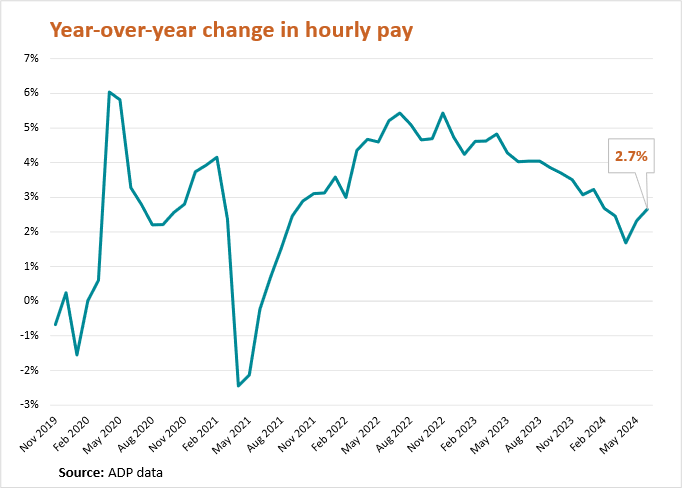

ADP Research analyzed the median monthly pay of more 22 million individuals starting a year before the pandemic shutdown in March 2020. As the chart below shows, year-over year wage gains were negative in January 2020 and flat in February 2020.

In the early months of the pandemic, year-over-year wage growth jumped to more than 5 percent. That’s because the bulk of job losses hit low-paid workers who were tied to customer-facing industries such as leisure and hospitality. These losses caused average median wages to surge.

As low-paid workers returned to the job market in 2022, wage growth stalled at higher levels before surrendering to a steady decline in 2023. Post-pandemic year-over-year wage gains bottomed out in April at 1.7 percent and now are heading up again, reaching 2.3 percent and 2.7 percent in May and June, respectively.

Even though wage growth is down significantly over the past two years, it remains elevated compared to the immediate pre-pandemic period, and it’s ticking up again.

The role of hiring

A big change in the labor market over the past four years has been the composition of the workforce and the hiring mix of low- and higher-paid workers.

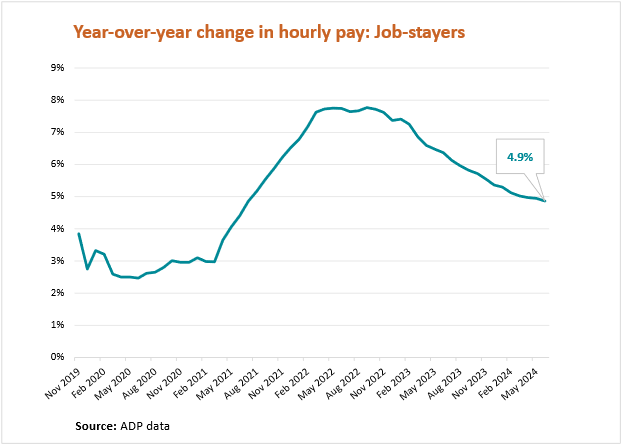

In the next chart we remove these cohort effects, which muddy the water on wage trends. ADP’s ability to track the anonymized pay data of unique workers allows us to track the annual pay gains of individuals, including people who haven’t changed jobs recently. In February 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns, year-over-year pay gains for people who had been in the same job for at least 12 months was 3.2 percent.

Median pay for these job-stayers peaked at 7.8 percent in the spring of 2022 and hovered near that level before starting to decline in the spring of 2023.

This year, after hovering above 5 percent in the first five months of 2024, pay growth for job-stayers was at 4.9 percent in June. That’s the slowest pace of gains since August 2021, but it’s more than 1.5 percentage points greater than the rate of pay growth we saw before the pandemic.

The role of wages and hiring

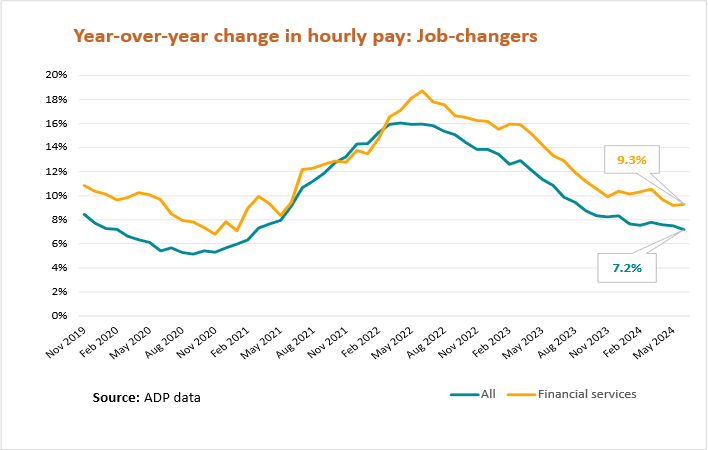

ADP data also allows us to analyze the pay differential between a worker’s old job and their new one. Pay for these job-changers is more sensitive to local economic conditions.

Before the pandemic, a person starting a new job typically received a 7 percent pay increase. Like job-stayers, these job-changers saw their pay growth peak in the spring of 2022, reaching 16.1 percent before starting to slow last year.

In June, pay gains for job-changers were 7.7 percent, not far from the 7.2 percent gains they enjoyed prior to the pandemic.

The similarity of these numbers, however, belies an important shift. For most of the pandemic, low- wage workers were driving pay gains. Now, they’re not.

To illustrate this change, look at pay in the lowest-paid super sector, leisure and hospitality. After median pay growth for these workers surged between August 2021 and March 2022, pay growth for job-switchers in the industry has fallen below the rate for the labor market as a whole. In June, pay growth for job-switchers in leisure and hospitality stood at 3.1 percent, significantly below the nearly 5 percent they reported immediately preceding the pandemic.

In contrast, workers in sectors with higher median pay are seeing stronger pay growth. In construction, financial activities, and manufacturing, for example, median pay was up 9 percent in June year-over-year. Median annual pay in these sectors is more than double that of leisure and hospitality workers.

My Take

Wages are the bridge between the job market and inflation. A common narrative for economists and market watchers is that if wages “go back to normal”, so will inflation.

But even though pay gains are slowing, the drivers of that trend have changed. The lowest-paid job-switchers are no longer in the driver’s seat. High earners are the ones with their foot on the accelerator.

Everyone wants to know what it will take for the Fed to reach its 2 percent inflation target. But as we continue to recover from the pandemic, the role of wages, an important player in the inflation calculus, have become much more complicated to divine.

The week

Monday: ADP Research releases data on promotions. Headlines about the labor market typically focus on job openings, hires, quits, and layoffs. The complicated question of career development—in particular the pace that people rise through the management ranks—gets less attention.

We also release new findings showing that Gen Z and young millennials would rather be unemployed than unhappy.

Thursday: The Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the Consumer Price Index, a measure of inflation. We’ll be watching the shelter component, which has doggedly slowed any retreat in consumer inflation.

Friday: The BLS releases the Produce Price Index. While not as attention-grabbing as consumer prices, producer prices can provide an important gut check on the direction of inflation.

Another gut check will come from the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment survey. Downbeat consumer sentiment is starting to translate into slower consumer spending, which is a double edge sword for the economy. Slower spending may slow inflation but also growth in the second half of the year.