Main Street Macro: The landing: It’s not how, it’s where

September 09, 2024

|

For the last two years, economists and market strategists have been intensely engaged in a debate over this question: Is the U.S. economy headed for a hard or soft landing?

The how is one thing, but much less attention has been paid to where the economy will land. But after a week of weaker-than-expected job data, the economy’s destination is coming into focus.

Here’s a deep dive into how the U.S. labor market is changing.

Less churn, slower hiring

One hallmark of the U.S. labor market has been its dynamism. A dynamic labor market affords workers the option of switching to jobs that offer better opportunities. It gives employers the ability to grow and shrink their workforce in concert with changing economic and industry conditions.

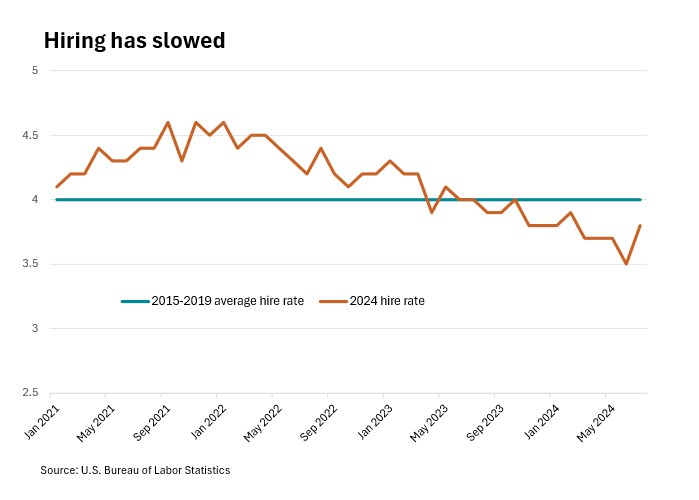

Dynamism has slowed over the past three years. Employees are less likely to be let go, but they also are less likely to quit their jobs for better prospects. With turnover low, employers now have less need to replace departing workers.

This lack of churn is new and different from the way things were before the pandemic.

Labor market churn is defined as hirings, quits, separations, and replacements that occur in a short period of time.

Churn is a sign of a health. In good economic times, churn tends to be higher. A less-dynamic labor market means fewer job openings and slower hiring rate.

The Great Resignation of 2022 was an extreme example of labor market churn. In sharp contrast, July’s quits and layoffs both were below their 2019 levels. While the market has lost some churn, it’s not all bad news. Today’s hiring is being driven not by churn and replacement hiring, but employers that are growing their headcount.

Weakened manufacturing, normalizing services

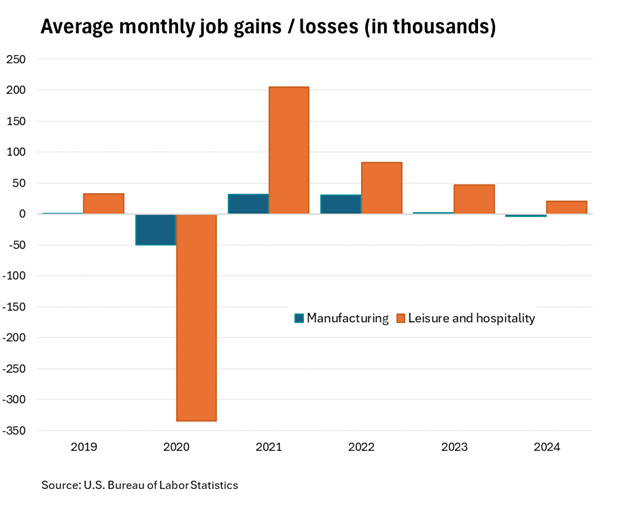

So far this year, average monthly job gains are just above where they were in the months leading into the pandemic. Service providers have averaged 170,000 jobs per month so far in 2024, compared to 159,000 in 2019, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Goods producers to date have averaged more than double their monthly 2019 gains, at 15,000 new jobs per month compared to 7,000.

One sector stands apart: Manufacturing.

Manufacturers showed weakness in the second half of 2019, losing jobs in each of the six months preceding the pandemic.

In 2024, manufacturing jobs have gone negative, with the sector shedding an average of 4,000 jobs each month, according to the BLS. This stands in contrast to leisure and hospitality, which has throttled back from outsized job gains, but continues to produce jobs.

Elevated but stable pay growth

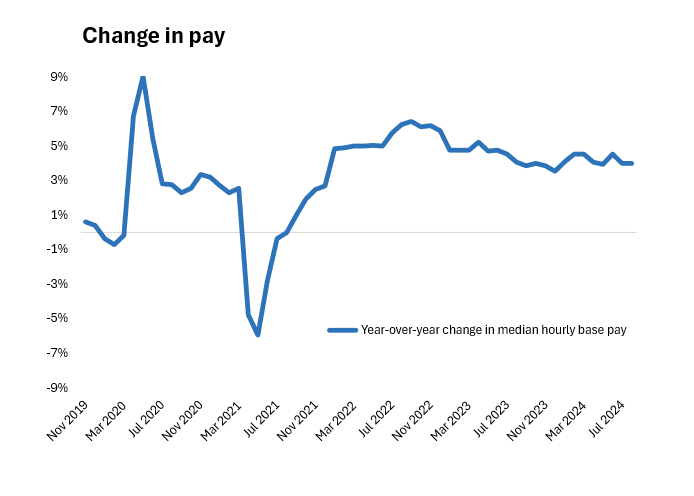

Last week’s ADP Pay Insights data showed that pay growth for job-stayers and job-changers is stabilizing after a dramatic post-pandemic slowdown. This data is based on 10 million workers whose pay we can track for 12 months or more.

For another hint of the labor market’s destination, we have data based on more than 20 million workers that dates to before the pandemic. This data includes all workers in ADP payroll data, both those whose pay we can track over a year or more and those whose pay we can’t.

In the five months leading into the pandemic, median base pay was flat to negative. Pay then surged in the pandemic’s aftermath when low-paid workers who had been laid off in large numbers were rehired or replaced.

These big swings in employment have since settled, and year-over-year hourly wage growth was stable at 4 percent in July and August. This is a much higher pace of growth than we saw during the months preceding the pandemic, when the typical worker saw little to no pay growth.

My take

Soft or hard, a labor market landing is close at hand. But the destination has changed since we were here last.

The U.S. labor market is less dynamic than it once was, with tepid hiring and workers who are less inclined to switch employers. Weaker manufacturing is a persistent drag on job growth.

Still, today’s labor market has a distinct advantage over its pre-pandemic past. Wage growth is much stronger and more stable. As such, wages are unlikely to trigger another bout of too-high inflation.

It might not be a perfect landing, but on-the-ground conditions are healthy enough to support consumer spending and economic growth this year.

The Week Ahead

Monday: Jobs and inflation are the two factors of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking equation. A third factor worthy of attention is the consumer. Today, we get a look at consumer resilience in a cooling labor market with the central bank’s release of July consumer credit data.

Tuesday: The Consumer Price Index or CPI measure of inflation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics is the most important indicator of the week. It might influence the size of any Fed rate cut, be it 25 basis points or 50 basis points.

Wednesday: The Producer Price Index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics is a sidekick to the CPI. If the PPI comes in hotter than the CPI, it could mean higher consumer prices down the road.

Friday: The week ends with consumer sentiment survey results from the University of Michigan. The link between how consumers feel (dismal) and their spending (resilient) has been weak. I’ll be looking to see whether slowing labor market conditions or slower inflation is more likely to make a difference in consumer sentiment.