Main Street Macro: Chasing Growth

September 25, 2023

|

This week, in the absence of a video, I’d like to set a scene with words. Imagine you’re a hero, tracking a villain dead-set on mayhem. The fate of the economy hangs on your every move.

Fraught with more tension than The Dark Knight, central banks around the world have been doing just that, turning their laser sights on interest rates as they try to chase down high inflation. Every decision carries high stakes, with the threat of a slowing economy menacing at every turn. It’s a fact that many economies don’t just fall into recession; they’re driven there by central banks that hike rates too aggressively.

In that way, central banks are a lot like our big-screen heroes: They catch the bad guy and save the day, but only after a high-speed chase that leaves flaming cars and damaged buildings in its wake. When central banks are in hot pursuit of inflation, economic growth typically pays the price in the short term.

Last week, the Federal Reserve paused its run of interest rate increases, but suggested it would restart them later this year. Investors (Main Street’s Wall Street neighbors) were disappointed. Major stock indices slumped on the news.

Higher interest rates increase borrowing costs on Main Street and reduce the value of capital investment on Wall Street. But over the long term, how enduring are the effects of Fed tightening? Will incremental increases made in the next three months matter 10 years from now?

The Fed’s Outlook

The Fed itself has some thoughts on that. Last week, the central bank published its best guess of what the economy will look like over the next few years. It also estimated what level of interest rates would be necessary to get us there.

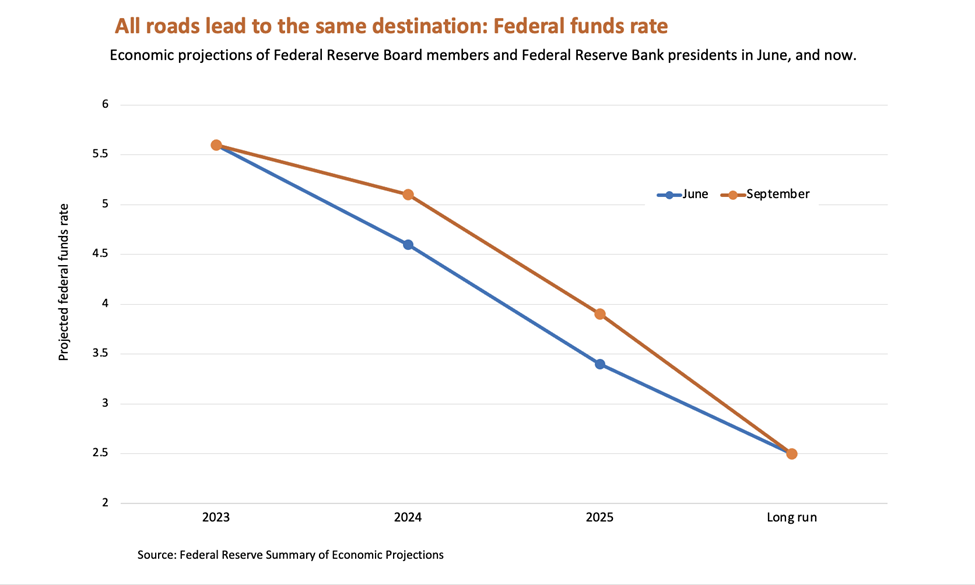

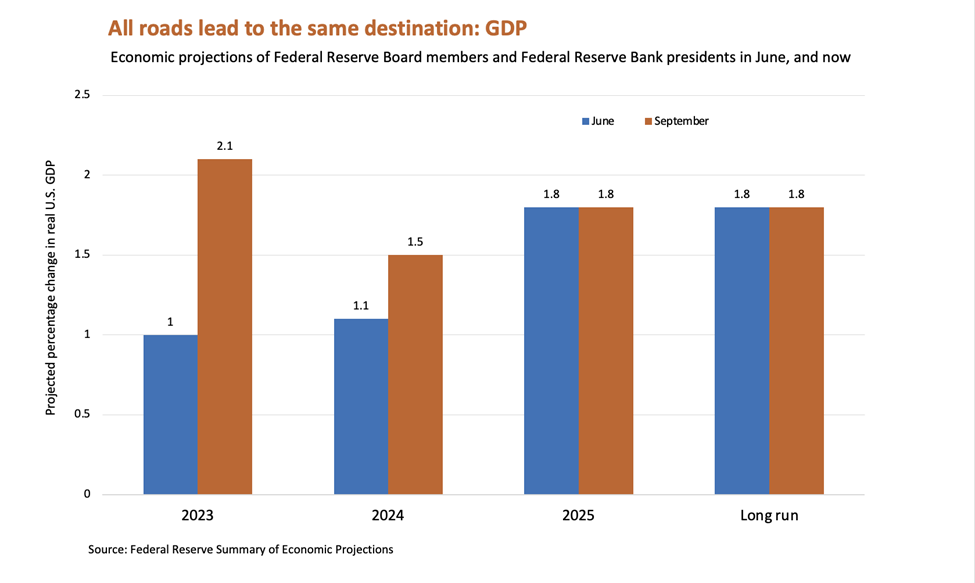

From the bank’s perspective, our current inflation chase has inflicted minimal damage to the broader economy. In fact, the economy seems to be getting stronger, even as we live with higher rates. In June, the Fed projected 1 percent growth for 2023. In September, policymakers were much more optimistic, projecting 2023 growth of 2 percent. By 2025, under both the September and June outlooks, the Fed thinks the economy will grow at its long-run rate of 1.8 percent. Fed policymakers also think interest rates over the next three years will be higher than what they predicted in June.

While the central bank expects interest rates to remain at higher levels in the near term, the rates predicted in June and September converge in 2025. That means that in the long run, there’s no difference between the June and September projections.

My take

The fact that the Fed thinks all interest rate paths lead to the same growth rate destination is no coincidence. It taps into a long-held economic theory that monetary policy is neutral in the long run. According to theory, the Fed can’t affect the real economy or its productive capacity. It can only alter the price of goods and services and the wages workers receive to produce them.

That thinking, however, might not stand the test of time. New research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco challenges the concept of long-run neutrality. It suggests that monetary policy indeed can affect the economy by increasing the cost of investment and slowing the ability of workers to become more productive.

Higher interest rates, for example, could limit the ability of companies to invest in the machines, employee training, and technology that make workers more productive and businesses more profitable. In short, the things that fuel economic growth.

So if monetary policy affects capital investment and, in turn, productivity, then we might get a future economy stunted by higher-for-longer interest rates. Or maybe long-held theories will prevail, and we won’t.

We won’t know the outcome of this cliffhanger for years. What matters now for Main Street is that the Fed is still chasing down inflation, despite a pause in the action this month.

Luckily, damage to the economy thus far has been minimal. But we’re still waiting for the final blow that takes out the inflation villain for good – or at least until the next sequel.