MainStreet Macro: The next inflation risk

May 15, 2023

|

Lately, I’m reminded of inflation during my morning exercise class. While the first 50 (OK, 35) sit-ups are fast and easy, after that my pace starts to slow. By 60 reps, I’ve gone from fast and easy to slow and irregular.

Last week, new data showed that the rate of inflation is slowing, but it’s taking its sweet time. Pandemic pressures have eased their grip on prices, but we might be running straight into a new headwind: America’s aging workforce.

The Consumer Price Index, a broad measure of what people pay for goods and services, rose 4.9 percent in April from a year earlier, just a smidge less than the 5 percent pace recorded in March. The narrower measure of core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, was 5.5 percent, down from 5.6 percent.

The Federal Reserve has been raising rates for more than a year. That and the easing of pandemic supply chain woes have gone a long way toward pushing the rate of inflation down significantly from its recent 9.1 percent peak.

But while inflation is moving toward the Fed’s 2 percent target, progress is slowing.

The next inflation worry

Future inflation is likely to be driven by demographics more than economics. In the decade-long expansion that preceded the pandemic, it was easy for the Fed to hit its 2 percent inflation target. In fact, economists for a while were worried that inflation was too low.

Now there’s worry that inflation could bottom out at 3 percent or more, well above the central bank’s target.

The difference between now and then isn’t just economic. In the long term the path of inflation is shaped by demographics.

Academic research has shown that an increase in the share of working adults lowers inflation, while a decrease in the share of working-age adults increases inflation.

In many advanced countries, including the U.S., the share of adults 65 and older is increasing. With more people aging out of their prime working years, labor shortages are likely to be more frequent and have a more enduring impact on prices.

If demographics are destiny, then the aging U.S. labor force is signaling a future of higher inflation.

Early retirements and a shrinking workforce

Since 2000, people aged 65 and older have stayed in the workforce longer. U.S. life expectancy has been rising for decades, and fewer people want to spend 15 years or more in retirement. This trend has coincided with a period of low inflation.

After the pandemic, however, the late-retirement trend ended abruptly. An estimated 2.2. million more people retired earlier than they would have had it not been for the health crisis, according to Fed research. Most of these new retirees were 65 and older.

While prime-age workers – people 25 to 55 – have returned to work at even higher rates than before the pandemic, labor participation among the older population is down nearly 2 percent.

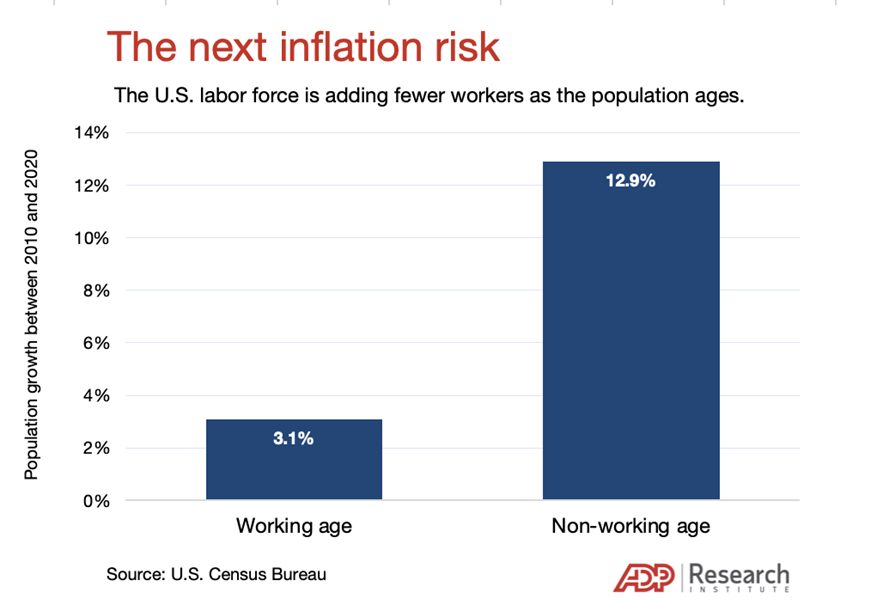

At the same time, the growth of the non-working-age population – people 14 and younger or 65 and older – has outpaced the growth of the working-age population.

The non-working-age population grew by 13.1 million in the last 10 years, a 12.9 percent increase. The working-age population increased by less than half that number, 6.4 million or 3.1 percent, according to the Census Bureau.

These demographics affect the supply of workers. Over the next decade, the workforce is expected to grow at half the rate of the previous decade.

My Take

I write this blog after returning from my morning exercise class. I’m not sure how many sit-ups I did, but it was somewhere between the 50 (OK, 35) that I can do easily, and my 100-rep target. My hope is that even as I get older, if I keep working at it, reaching my target will become easier.

There’s a risk, likewise, that the aging U.S. labor force will prevent inflation from reaching its 2 percent target. That risk is reduced if older workers keep working as well. There is reason for hope. When it comes to inflation, age is more than just a number. With remote and hybrid work options, improved life expectancy, and labor-enhancing technology, older workers could have more professional opportunities in the future, not fewer. If those opportunities come to fruition, our demographic destiny might help inflation reach its target.