MainStreet Macro: March Jobs Data: A Return to Balance

April 10, 2023

|

Last week delivered a fresh round of jobs data for February and March. Today, we’ll catch up on the numbers and what they say about the current state of the labor market. All told, it’s mostly good news.

Employers pulled back on job postings

Employers posted 632,000 fewer jobs in February than they did in January, a 9 percent decrease, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on Tuesday. The biggest drops were in professional and business services (-278,000); health care and social assistance (-150,000); and transportation, warehousing, and utilities (-145,000).

It was the first time since May 2021 that employers posted fewer than 10 million job openings. Instead of 1.9 job openings for every unemployed worker, the labor market has loosened a smidge, to 1.7 jobs per available worker.

Small employers led hiring

A day later, the ADP National Employment Report showed a slowdown in private sector hiring in March, to 145,000 net new jobs from a revised 261,000 in February.

Small establishments – those with fewer than 50 workers – led the expansion. They created 100,000 jobs in March, while medium and large employers created 33,000 and 10,000 jobs, respectively.

Pay growth slowed

The downshift in private-sector job gains was matched by a slowdown in wage growth. ADP’s Pay Insights data showed that pay gains for job stayers fell to 6.9 percent over the last 12 months. It was the first time since January 2022 that the pace of pay growth was less than 7 percent. For job changers, year-over-year pay growth slowed, to 14.2 percent in March from 14.4 percent in February.

Layoffs increased

Every Thursday, we get a fresh read on initial jobless claims, a proxy for layoffs. Lately, this measure is being watched particularly closely as several big companies conduct layoffs.

The last four weeks of initial claims showed a slight uptick, increasing to an average of 242,000 in March from 218,500 in February. Despite all the headlines about layoffs, by this measure the aggregate change in job loss is tiny and unemployment remains near historical lows.

The unemployment rate dropped – again

Finally, we learned on Friday that the unemployment rate dropped to 3.5 percent in March from 3.6 percent in February, remaining near historical lows, according to the BLS non-farm payrolls report. And more workers rejoined the job market, boosting labor force participation to its highest level since the pandemic.

Overall, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported an increase of 236,00 private- and public-sector jobs.

What it all means

To simplify this data, let’s go back to economic fundamentals: labor supply and demand. (Before all of you Econ 101 survivors groan and shut down your computers, hear me out.)

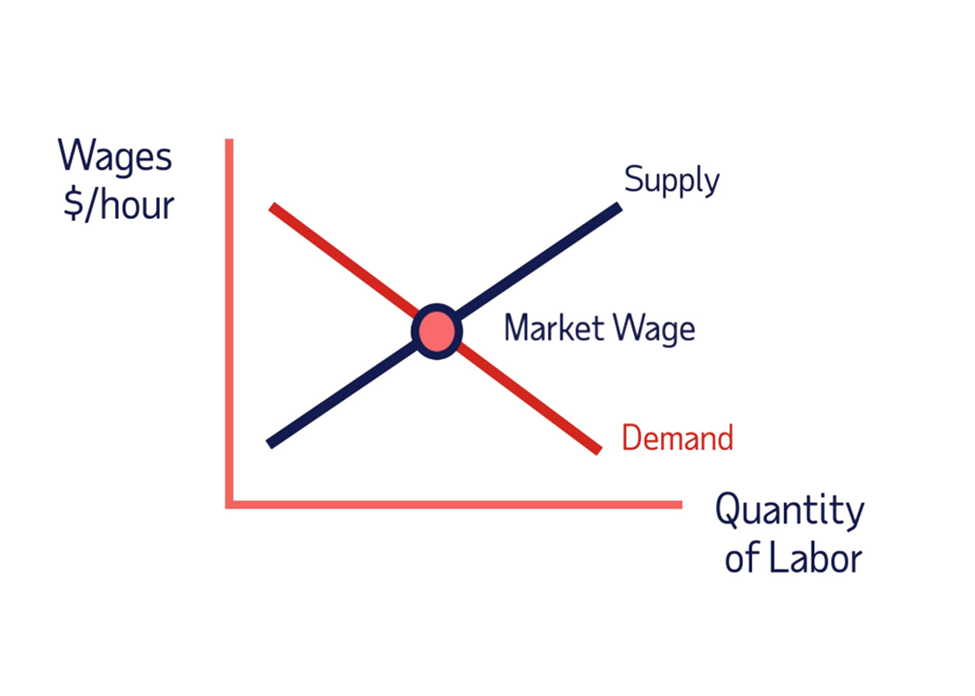

Below is a simple chart. The x axis shows the quantity of labor supplied; the y axis is hourly wages.

Labor supply is the number of people who are willing and able to work and the number of hours they’re willing to work. Not surprisingly, the higher the wage, the more hours people are willing to supply to the market.

Labor demand is the quantity of work that employers are willing to pay for at a given wage. Adding up all employers and all workers gives us the aggregate demand and supply in the economy. The intersection of those two lines produces the equilibrium or market wage.

Before the pandemic, wages grew by less than 3 percent, in line with the growth of the economy and the pace of inflation at the time. Labor demand and supply were in balance.

The shock of the pandemic threw demand and supply out of whack. As the economy recovered, labor supply tightened, causing a shortage of workers and increasing the amount of labor demand.

That’s why wages have grown so rapidly over the past year. As employers struggled to find qualified people and employee turnover increased, the pace of wage growth more than doubled.

Pay growth now is starting to moderate as supply and demand come back into balance. ADP’s latest report shows that year-over-year pay growth fell below 7 percent for the first time since January 2022. Inflation also has fallen, which helps both employers and employees.

My Take

Given the U.S. economy’s complexity and diversity, no single metric can completely capture the economy’s shifting dynamics. But taken as a whole, we see a labor market that is coming into balance after a year of staggering job loss in 2020 and a year of extremely intense hiring two years later.

In 2023, with headcounts mostly restored, employers can stop scrambling and return their focus to what matters longer term – sustainable growth. Growth isn’t sustainable if it drives up inflation, and for that the economy needs a balanced labor market.

If last week’s data was any indication, we’re headed in that direction.