MainStreet Macro: Robots need a human hand

November 28, 2022

|

Before the holiday break, I left MainStreet Macro readers with a bit of a cliffhanger. We had just heard about layoffs at some of the biggest technology companies, a sector that has seen a lot of growth over the past several years.

Technology has long held out the promise of lower prices and improved efficiency. But as the sector matures, it hasn’t fully delivered on those hopes. Inflation is way above historical averages and productivity has lagged for years.

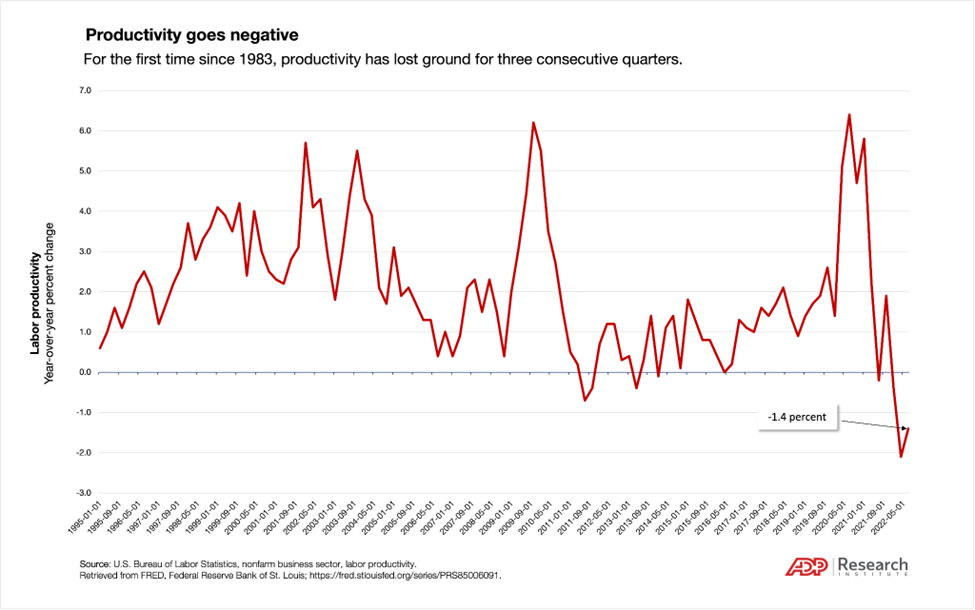

Productivity growth has, in fact, slowed from an average of 2.8 percent per year in the decade ending in 2005 to 1.3 percent per year between 2006 and 2019, when the pandemic began.

More recently, output per hours worked has been in outright decline. In 2022, the year-over-year change in productivity has been negative for three straight quarters. We haven’t seen that kind of drop since 1983.

In the third quarter of 2022, workers put in 3.4 hours more than they did a year earlier, but produced only 1.9 percent more output. Ouch!

Researchers estimate that this slowdown has made all of us $9,000 poorer per year than we would have been if productivity growth had maintained its earlier pace.

So why has productivity sagged while technology boomed? Here are three possible reasons.

We’re measuring things wrong

Economists define productivity as output per hours worked. Output is the quantity of goods and services produced in a specific time period.

To see how the numbers might not line up, take a look at your phone.

Is it really a phone? Or is it a camera? Or a stereo, streaming device, library, financial manager, social forum, bank, wellness tool, gaming console? The list, truly, is endless.

Maybe the economy just seems less productive on paper because we’re getting all these services bundled into a single device that we don’t know how to classify.

Our old-school way of measuring things might be underselling technology’s contributions to the economy. That’s not a technology problem about productivity. It’s an accounting problem.

It’s too soon

Cloud computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, digital services – all these innovations are relatively recent newcomers in the sweep of economic history. It might take more time for technology’s impact to be felt in, say, hospitality, education, and other consumer sectors.

While technology has played big roles in health care and manufacturing, it’s had little effect in residential construction, for example, and housing is one big driver of inflation.

Over time, it’s possible that technological advances will seep deeper into the fabric of the economy to lower costs and boost output in a more broad-based way.

Humans aren’t prepared

Just because we have all this great technology doesn’t mean it’s being deployed to maximum efficiency.

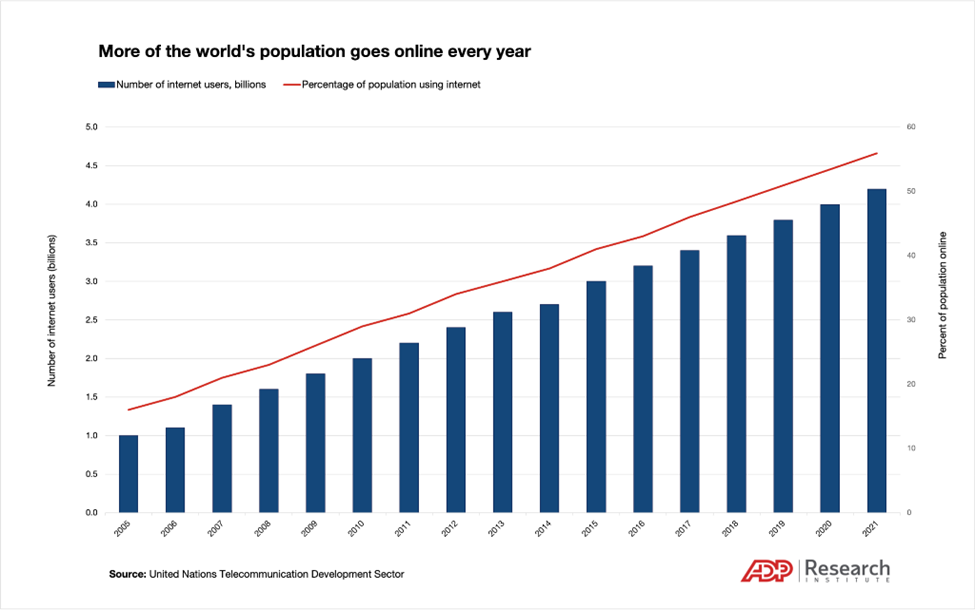

Millions of people join the digital economy every year, and more than half the world’s population is now online. We can expect demand for technology to grow at an equally fast clip.

To meet this demand, employers need to incorporate the latest innovations into their operations and processes And that means workers will need to develop tech-forward skill sets.

From the industrial revolution through today, public-private partnerships have led to successful apprentice programs to upskill workers. These partnership programs should be expanded to create opportunities for skill development and training in preparation for technology-oriented jobs.

If we want to boost productivity, the workforce needs to be prepared for a new economy in which tech plays an even bigger role than it does now.

My Take

I find this last reason the most compelling in the debate over productivity.

To get the biggest productivity bang for the buck, technology needs people. It’s not just about automation. It’s about using technology to make people more efficient.

It’s this pairing of people and technology that ultimately will lead to more workers being more productive. And that will increase not only output, but standards of living for everyone.